From Indiewire.com

Why the death of García Márquez is a loss for the world of film.

One of the things "/bent" is looking to explore in the coming months is the ever-potent relationship between literature, poetry and film. After the death this week of Gabriel Garcia Marquez we asked the poet Emma Scully Jones to reflect on his life and work in this context.

Marquez at the Movies - by Emma Scully Jones

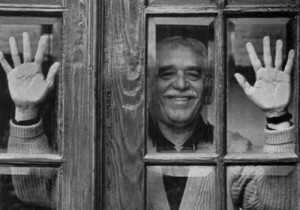

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the Colombian writer and Nobel Laureate whose 1967 novel One Hundred Years of Solitude is a seminal text of ‘magical realism’, has died. He was 87. Obituaries and tributes abound. But we should also to say goodbye to a slightly different Marquez than the familiar journalist-turned-novelist whose work helped put Latin American writing firmly on the literary map. We should say goodbye to Marquez the film-lover, Marquez the screenwriter, Marquez the cinematic thinker.

The death of Marquez is a loss to the collective human imagination. But here’s why it’s also a special loss to film.

Marquez was a champion of filmmaking and filmmakers

In the 1950s Marquez studied directing at the Experimental Film School in Rome and never forgot his early ambition to be a film director. 'I felt that cinema was a medium which had no limitations and in which everything was possible,' he said in an interview with The Paris Review. 'But there's a big limitation in cinema in that it's an industrial art, a whole industry. It's very difficult to express in cinema what you really want to say.' In the 60s Marquez moved to Mexico to write film scripts, and as a young journalist he was an avid movie reviewer. In this he joins another South American literary great, the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, who wrote this about "Citizen Kane": 'it is not intelligent, though it is a work of genius'. Sadly, Marquez film criticism has yet to be collected.

Marquez ambitions as a filmmaker may have waned over the years – 'my relation with it [cinema] is like that of a couple who can’t live separated, but who can’t live together either,' he told The Paris Review – but he remained an ardent champion of independent filmmaking, and in the early 1980s used his financial security as a writer to found an International Film School near Havana, with the blessing of his friend Fidel Castro.

The screen becomes part of the page

Marquez also had respect for, and dabbled in writing for, soap operas. This, he argued, was the way to reach the widest audience and meet their deep human need for narrative. This is important. Not only does it show that Marquez was no snob, but it also gives us an angle into one of the chief strengths of his writing: its tendency to blend, with seamless ease, registers of 'high' and 'low' culture. Marquez was at home with the telenovela as he was with Cervantes. And there are many that would argue that the overblown plots and noonday melodrama of most telenovelas are their own special blend of magic realism. Certainly Marquez tendency to present fantastic events with narrative economy might owe something to these melodramas which play out, like tiny Greek tragedies, in the background of Mexican domestic spaces (Mexico was Marquez’s adopted home).

Added to this, Marquez described himself as 'not an intellectual' or 'abstract thinker', noting that many of his novels had as their root a photograph or an image, rather than an idea. In this he shares ground with many directors, who see their work as visual and emotional, and possessing ocular logics of association, visual ‘arguments’. Movies aren’t usually the children of reason.

Hollywood is yet to adapt Marquez successfully

There have been a few adaptations of Marquez's novels, mainly in the Spanish language. In 1983 the movie "Erendira", based on Marquez's 70s novella 'Innocent Erendira and Her Heartless Grandmother' appeared, with a screenplay by Marquez himself (he’d written the screenplay years earlier, but it had been lost: when the film was mooted, he reproduced it from memory). The New York Times described the film as having a 'dreamy if monotonous charm', noting that 'one decodes Mr. Garcia Marquez at one's own risk.'

In 1987, Italian director Francesco Rosi released "Chronicle of a Death Foretold", based on Marquez's 1981 novella of the same name. The novella’s structure, as a pseudo-journalistic account, shows Marquez anticipate the mockumentary. The 1999 adaptation by Arturo Ripstein of Marquez’s novel No One Writes to the Colonel had its premiere at Cannes and met with critical success, as did Costa Rican director Hilda Hidalgo’s 2010 debut "Of Love and Other Demons', based on Marquez's 1994 novel of the same name.

Yet Hollywood has so far adapted only one Márquez novel: the 2007 turkey, "Love in the Time of Cholera", starring Javier Bardem. The Guardian called it a 'softcore Captain Corelli' and a 'film to be strictly quarantined'. Other Hollywood forays into magic realism – like the 1993 film adaptation of Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits, which starred, promisingly, Meryl Streep and Jeremy Irons – are also bust. At first glance it seems odd that books like these, which are eminently cinematic, and are filled with fantastic events and striking visual tableaux, haven’t been more readily translated to the big screen. But maybe it’s the desire to be overtly ‘fantastic’ that has been the problem.

One of Marquez's great gifts was to yoke the fantastic to the everyday, the overblown event to the tiny realistic detail. (Think of his character Remedios the Beautiful ascending to heaven as she prosaically pegs out the washing in One Hundred Years of Solitude, for example). Marquez identified strongly with the indigenous, black, and Spanish traditions and mythologies of his native Colombia, where the fantastic (he said) is everyday, unremarkable. A great influence on his prose was the storytelling style of his grandmother, who narrated miraculous events with deadpan, matter-of-fact delivery. Maybe Hollywood should learn from the novelist: that when it comes to the fantastic, less is more. If you’re showing roses raining from the sky, or a flying carpet ride, then the visual is speaking for you: you don’t need a swelling soundtrack or mannered direction. If you’re in love with reality, then reality is fantastic. Present it all as realism.

Marquez himself said this of the believability of his fiction: '[There’s] a journalistic trick which you can also apply to literature. For example, if you say that there are elephants flying in the sky, people are not going to believe you. But if you say that there are four hundred and twenty-five elephants flying in the sky, people will probably believe you.' With new capabilities in CGI, maybe now is the time for believable, realistic adaptations of Marquez’s literature of the fantastic. CGI, when done well, can make the most outrageous creature or event blend seamlessly and realistically with its everyday surroundings (think of the fictional, quiet, ominous new planet, glowing like a second moon in the night sky in "Melancholia" for example). It can make the transition from the prosaic to the fantastic so seamless that the difference between them becomes – as it was for Marquez – no great difference at all.

The death of Marquez is a loss to film. And maybe, when it comes to cinema, the fitting tributes to Marquez are still to come. That is, those movie adaptations of his works that share the spirit of the storytelling, not just its events, and show, with subtle astonishment, the fantastical qualities of daily life.

Emma Scully Jones’s first book, The Striped World, is published by Faber & Faber. She is a new tweeter and you can follow her at @emmascullyjones.